The Holy Names of Jesus and Mary from Europe to Mexico

Mexican masters, Miter, Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Tesoro dei Granduchi (Picture: Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut)

Contribución en actividades de investigación de Corinna T. Gallori

comparte

Between the end of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth century a somewhat peculiar image began to circulate throughout Europe. It featured a monogram composed of the superimposed and interlaced letters of the names of Jesus (ihs) and Mary (ma), in which diverse images of objects and figures recalling various stages of the Passion were inserted. This unusual image, probably created in France, was widely disseminated through its reproduction as the subject of several prints. In all the known variations, the letters always intertwine in the same way, and the crucified Christ, mourning Mary and John are always depicted in the ‘ih’, but the other scenes from the Passion could subtly vary.

The most widely reproduced and appreciated (both visually and devotionally) version of the Holy Names in Europe featured a Mass of St. Gregory in the lower section of the ‘i’, is featured in an Italian woodcut from Lombardy (ALU 00010.1, http://archivi.cini.it:80/cini-web/storiaarte/detail/843/stampa-843.html, y ALU 00010.2, http://archivi.cini.it:80/cini-web/storiaarte/detail/1439/stampa-1439.html), a fine French printed image dated 1510–1520 (Metropolitan Museum, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/337963), and a lost print once in the collection of Ferdinand Columbus, known only thanks to his inventory. A number of subsequent artistic derivations contributed to the success of this particular version of the monogram.

Through the wide circulation of these printed derivations, the Holy Names reached Mexico, probably thanks to printer Giovanni Paoli, active from 1539, who was a native of the Brescia province, exactly the area in which the Lombard Holy Names’ print was circulating. In Mexico, the Holy Names were reproduced in five miters crafted in the featherwork technique. Although European prints must have provided a model, the Mexican artists adapted their source images in innovative ways.

The monogram in three of the miters, now preserved in the Tesoro dei Granduchi in Florence, in the El Escorial, and in the Musée des Tissus et des Arts Décoratifs in Lyon, combines motifs drawn from several additional sources. The Mass of Saint Gregory, the Evangelists, and some Arma Christi are depicted in all three miters, according to the prints from Lombardy and the Metropolitan Museum that include the Mass of Saint Gregory, but fewer instruments are represented and the arrangement is completely different. The Christ at the Column probably reprises an engraving by Adamo Scultori, that was based in turn on the Flagellation by Sebastiano del Piombo in the Borgherini Chapel in San Pietro in Montorio in Rome. The episodes from the Passion feature some unexpected scenes, namely the Washing of Feet, the Last Supper, and the Arrest of Christ, all inserted into the lower border. Generally, in Holy Names’ prints, the Passion cycle starts in the upper section of the ‘i’ with either the Prayer in the garden, as in one version by French artist Jehan Bézart (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b69396669.item), or the Capture of Christ, as in all the derivations from the suggested lost prototype, and ends with the Crucifixion. The three scenes added in the lower margin act as a preamble to the actual Passion cycle depicted in the intertwined ihs/ma, and are unusual as they extend the narrative sequence outside the letters. It is possible to identify the source for at least one of the additional episodes, and, as the Christ at the column, it does not belong to the Holy Names’ tradition. The Washing of the Feet seems to copy in reverse a vignette by Liewen de Witte belonging to Willelm van Branteghem’s Dat leuen ons Heeren Christi Iesu (Antwerp, 1537).

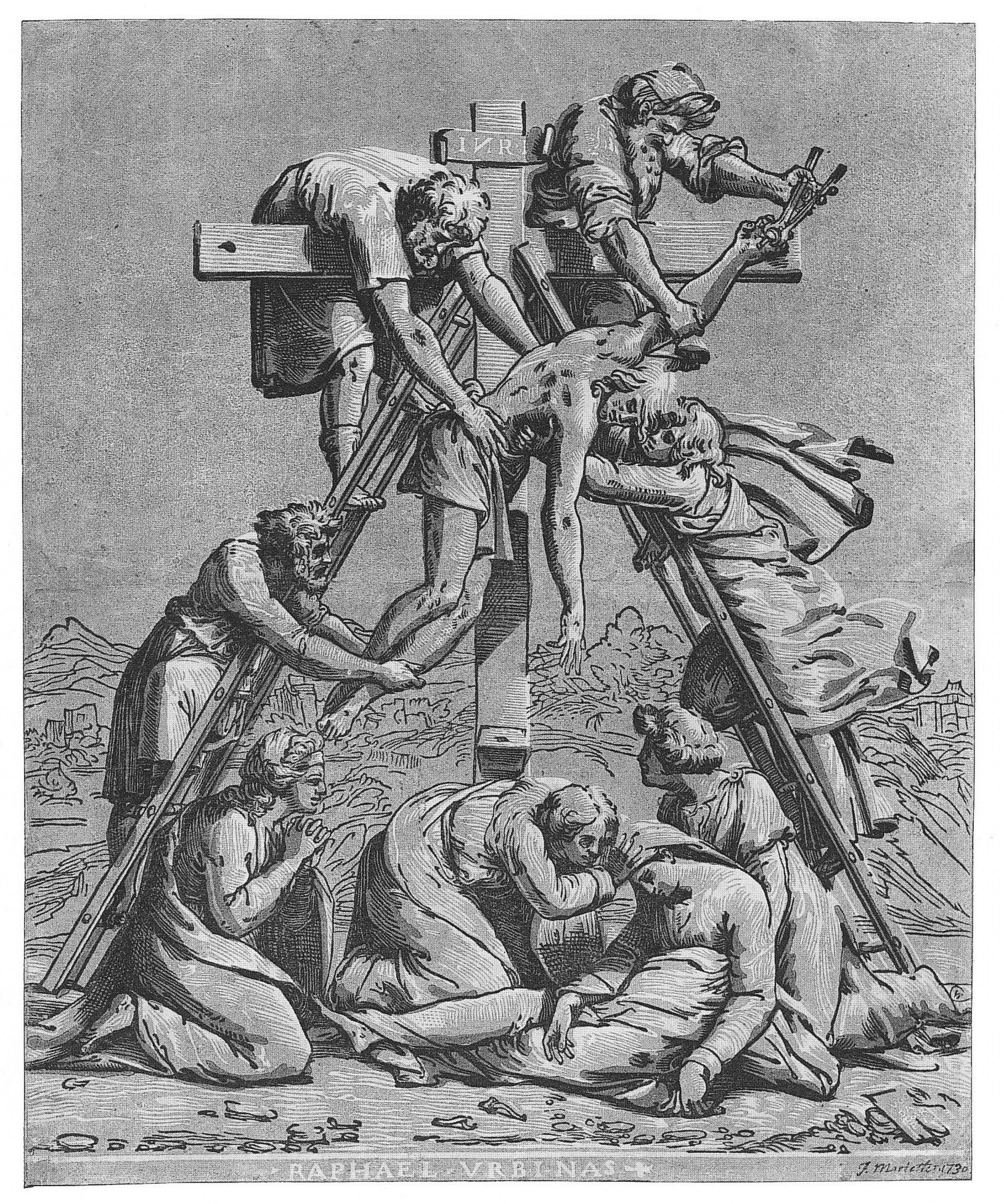

The tendency to combine in a single image elements found in diverse artistic sources is even more evident in the Holy Names on the reverse of the three miters, where we find a completely unexpected version. In the letters of the Holy Names there are scenes ranging from Descent from the Cross to the Incredulity of Saint Thomas, in addition to some pictorial elements completely alien to the story of the Passion, while the Entombment, the Pietà, and Christ in Limbo appear sequentially in the border. It is thus evident that the monogram appearing on the back side completes the cycle begun on the front. As there is no known print showing the Holy Names that could have served as a model for these narrative scenes, the artists probably created an entirely new image, experimenting with the insertion of new scenes both inside and around the interlaced letters. To visualize these new episodes, other engravings were used. The Descent from the Cross and the image that appears below it, Mary Consoled by the Women, are both derived from an image made by Raphael, disseminated in a chiaroscuro woodcut by Ugo da Carpi around 1520–1523, which I believe was the source for the miters, and in an engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi. In the Trinity, the Christ held by angels shows in reverse some figures extracted from the celebrated Pietà drawn by Michelangelo for Vittoria Colonna, an image that began to be disseminated as a print in 1546.

The creators of the miters thus devised a decidedly original pastiche, employing a figurative schema and adapting it, taking full advantage of the artistic potential of the image itself. However, this operative strategy has resulted in noticeable differences in the conception of the monogram between the different versions: episodes of the Passion are no longer represented through faces or other allusive elements; instead they have been converted into narrative vignettes that are sometimes placed outside the letters rather than within them.

The case of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary shows that the Mexican artists did not simply copy an image, but both adopted and adapted it. The miters show a different sense of narrative compared to their visual source. The latter narrate events via objects or body parts that are arranged in a chronological order, while the former do not. The front of the miters emphasizes the suffering Christ and features fewer phases of the Passion than the Lombard or the Metropolitan Museum’s prints; on the back, the episodes are represented in their entirety. On both sides the chronological order is not respected. Thus, in New Spain, the local artists played with the intertwined letters, creating a new version of the image; they choose how to narrate the story of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection. The sources they used varied, from the French prints of the Holy Names‘ to masters of the Italian Renaissance such as Raphael and Michelangelo. And, as the Washing of the Feet case shows, the search for visual sources used by Mexican artists should include not only single-leaf prints, but also book illustration and, most likely, other works of art. However, the images should also be related to other issues, such as the expansion of cults, history of printmaking in Mexico, or other events that might lead to a better understanding of the choices the artists made in designing and or creating the miters.

Para saber más:

Gallori, Corinna Tania. “From Paper to Feathers: The Holy Names of Jesus and Mary from Europe to Mexico”. En Images take Flight: Feather Art in Mexico and Europe. München: Hirmer Verlag, 2015, pp. 310-319.

Cómo citar:

Corinna T. Gallori, «The Holy Names of Jesus and Mary from Europe to Mexico», Iconoteca CIRIMA: Circulación de la imagen en la geografía artística del mundo hispánico en la Edad Moderna, 2021. Consultado el FECHA. URL: https://cirima.web.uah.es/iconoteca/the-holy-names-of-jesus-and-mary-from-europe-to-mexico/